Piers Plowright – (Stowe, 1951-1956) – A TRIBUTE TO JB

Given in Stowe Chapel, Saturday 10th September 2011

Three snapshots of Joe:

First, the new master, arriving at Stowe in 1954, when he was 26 and I was nearly 17. Perhaps the comparative closeness in our ages made it easy to talk to this energising and open man with his intellectual enthusiasms, his striking clothes – the green trousers, the yellow and red ties, the black corduroy jacket – and the deep voice, almost that of a Russian bass. Not that you could take advantage of him; he was always in charge and quite up to the wiles and stratagems of ‘clever’ sixth-formers. But there was never that ‘must be careful what I say or reveal’ feeling that prevented ‘deep conversations’ with other masters, however inspiring.

Second, the opener of doors and windows. He must have taught me French literature, but what I really remember is Joe the stage director and impresario, bringing into my life – and many others’ – the scent and excitement of contemporary European Drama. He introduced me to Brecht, to Sartre, to Ionesco, and to Pirandello. In fact it was his 1955 production of Pirandello’s Henry IV [Enrico Quarte] with Brook Williams as a dangerously good Henry –‘Is he mad or isn’t he ?’, the usual Pirandellian question – that really woke me up to the excitements of acting, as we waited behind the scenes in the shabby old gymnasium for the play to begin. Joe had chosen to start the production in darkness and the opening to Gustav Holst’s ballet suite, ‘The Perfect Fool’, a sinister rising and falling theme on the trombones, which still sends shivers down my spine. As we stood there, waiting for the curtain, I remember thinking, ‘I want to be an actor’. I didn’t become one but that wasn’t Joe’s fault. He was an exemplary director, teaching us to listen to the text and to each other, and not to make the usual schoolboy mistake of signalling every emotion. To go, in other words for the truth of the character.

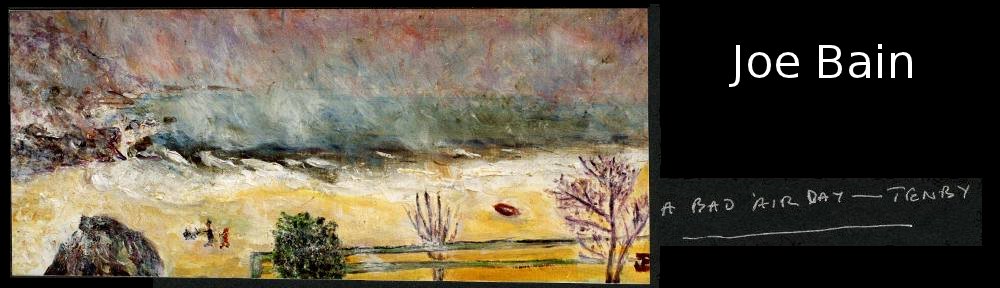

Third, my last day with him, in September 2005, in Tenby. There’d been a 50 year pause, and then he’d got in touch with me, and he and I and Brook Williams met a couple of times in London and picked up literary conversation and gossip, with an even greater ease than in the 1950s. After all we were now, all three, in our ‘third age’, and the difference between a late 60 year old and a late 70 year old is almost invisible.

After this, Joe and I exchanged our home made Christmas cards – his were spectacular – and planned a meeting in Tenby. It happened eventually because I booked myself into a retreat with the Cistercian brothers of Caldey Island. After five days of silence I was ready for one of Joe’s conversations. Which began in that remarkable house, 7 the Norton, crammed with books and paintings, and music books sprawling on and around the piano, continued in the Hope and Anchor pub where we ate fish and chips washed down with cider, took us into Albie the Pole’s second hand bookshop, floated us into St Mary’s Church, Joe showing me his favourite memorial tablets, carried us through tea at a café in Frog Street, and back to The Norton. And here we sat, as the light began to fade, talking about everything, glasses of wine at hand, and listening to the sound the doves made behind the fig tree in the garden, voices and wings. That fluttering and cooing was both very comforting and slightly sad – a kind of farewell. Which we had, for real, on Tenby station, as he waved my London train out. We spoke again on the telephone and through letters.

Not getting a card this Christmas, I rang in April, to hear of his hospital stay. But the voice was as strong as ever, and he said he might be coming to London in May…..It wasn’t to be, but, as friendships end, that September afternoon was perfect.

One of the people we talked about in The Norton kitchen was the poet, Louis MacNeice. Joe had written about him, and we both felt him to be hugely undervalued. So I’d like to end this tribute with MacNeice’s The Sunlight on the Garden. It was written in 1936, as Europe was going dark, and it’s a poem full of foreboding and pessimism. But it’s also shot through with delight in the moment and the ever-present possibility of bringing some light out of darkness. A good way I feel to say goodbye to a remarkable teacher and a remarkable man.

[The Sunlight on the Garden, written in Downshire Hill 1936, with Europe beginning to go dark, can be found in Louis MacNeice, ed. E.R. Dodds, Faber & Faber, 1966, p84 and in other editions.]