Frederic Raphael, in a letter to Priscilla Bain, 29 May 2011:

… I was aware of Joe as an unusual person from the very beginning of our acquaintance, which soon became a friendship. There was humour in the very timbre of his voice and in the rather dandyish (but never showy) posture to the world of 1950s Cambridge. He was humorous and sometimes fancifully sharp but his perception of human vanities (never in short supply) was linked with a modesty which made him a pitiless observer of ambition and opportunism on the part of others. He was more civilised – better read and generally cultivated – than other people I knew but he read, it seemed for his own edification, not in order to trump others.

I knew him mainly because of the college theatrical society. He was both accurate as a director and unassertive. He directed me in a production of Samson Agonistes (who can say what impelled us so unlikely a piece?) in the college chapel, where the acoustics were notoriously baffling. Somehow he knew that the only specific against inaudibility was not volume but careful diction, in particular the articulation of consonants. I learned the lesson pretty well and have often repeated it to professionals who were failing the key test of making simple words count.

I cannot say how often Joe and I were in contact over the years. Beetle and I knew him best in Cambridge where he came often to Jordan’s Yard and to the house we shared in my fourth year out in Montague Rd. It was there that he danced at once graceful and inebriated, to the light of a midnight candle, singing Falling in Love Again from The Blue Angel. He was often funny but never inelegant.

I never imagined that we should see each other often, nor did we, but I always enjoyed the conversations we shared. In recent years I have always smiled when talking to him, always enjoyed the clever idiosyncrasy of his civilised take on the absurd world in which we have become fortunate anachronisms, able to enjoy civilised things. Enjoyment was an inescapable element in being in touch with Joe, a rare, never rarefied man, a decent human being who I shall greatly miss.

Charlotte Eilenberg, in a letter to Priscilla Bain, cJune 2011::

… Joe was a formidable and remarkable figure in my teenage years in Kew and although I’ve had very little contact with him subsequently I felt him to be a kindred soul, perhaps because we shared the same birthday. It’s true that Joe’s patent enjoyment of crosswords and erudition, and his enormous pleasure in fine food, are not appetites I particularly share, and yet I observed him to be empathetic, shy, critical and reclusive, hugely relishing the company of – perhaps certain – others. A cross between Toad and Badger, in my mind, but on an altogether more epic and learned scale!

Peter Arbuthnot’s impressions of Chandos House, Stowe and Joe Bain, 24 August 2011:

When I came to Chandos (aged 13 in May 1964) we were in an unbelieveably successful sporting period….it is pretty hard to think of Joe as an enthusiastic ‘sports supporter’ but he was always loyally in evidence on the touchline (goodness knows what he was actually thinking while on the bleak Bourbon Fields in the rain ?)….our senior Chandos chaps (1964-66) were incredibly good all-rounders in every School team so we ‘cleaned-up’ an absurdly high proportion of all Stowe’s sports cups/trophies (at least double/triple any other house ?)….my House Photos of those years show a line of our School cups stretching from end-to-end and a (slightly smug) Joe flanked by our ‘sporting super-heroes’……even when, much later, I was his Head of House (Jan/Dec 1969) while also being Head of School we were still pretty successful on the sports front….due to Tony Sparshott’s prowess/enthusiasm on the sporting side (then followed by Stuart Morris’ similar amazing sporting talents) it must have seemed curious (to some other members of the Common Room ?) that such an intellectual/musical/theatrical man as Joe can have ruled over a house with such a dominance & prowess on the Sports front?

We did House Plays (I think) virtually every year that I was in Chandos (1964-1969) and because of my bumptious extrovert nature Joe plucked me for participation in them all (and for several of his School Plays) so that even now, retired after a career as an auctioneer at Christie’s, I am doing TV extra work for fun….however, due to Joe’s extraordinary & brilliant ’directing’ talents, Chandos under his guidance was extremely active on the theatrical side.

From (what at that time) seemed such a ‘confirmed bachelor’ came quite a sensitive pastoral side….my father had died in June 1967 during the Summer Term and Joe was always thereafter a very considerate (replacement) ‘father figure’ – without his help (influence) and encouragement I probably would never have got to Trinity (Cambridge). He beat me (fully deservedly !) several times in my early years but I, and no doubt MANY other Chandosians, undoubtedly will always owe Joe an immense amount for his freely-given intellectual bounty and humour….

Justin Wintle, in a letter to Priscilla Bain, 16 September 2011

… Like Peter Yapp’s, at least in his tribute, my first encounters with Joe were not altogether promising, not least because I had no aptitude for acting whatsoever, and I was a mediocre linguist. There were the two moments of threatened defenestration. The second time indeed occurred, as Peter related, when I asked Joe to tell me what he had written at the end of a second year essay: ‘It says I cannot read your handwriting, boy! Do that again and I’ll throw you out of the window!’ He did not relish being upstaged, and must have thought I was trying to do exactly that. (I wasn’t.) The first occasion was a year earlier, during a German class. He wanted to take us all off to his room to listen to Der Erlkonig. But two weeks before he’d done exactly the same, and I’d had enough of Der Erlkonig for one term, and said so. ‘I’ll throw you out of the window if you ever open your mouth again!’

As another of his former pupils Roddy Swanston put it to me the other day, Joe could be, and often was, ‘fiercely dominant’ in his younger days. There was also the occasion when I was struck by a loose fist in a rugby scrimmage, Joe eventually coming over to the touchline where I lay bleeding copiously from the nose to tell me that this was the first time I looked as if I belonged on a rugby pitch. But things got a whole lot better in the sixth form — and he was of course, along with the historian later turned MI6 figure Martin Cousins responsible for shoe-horning a rather lacklustre pupil into Oxford.

Joe taught me English A level for two years, including Othello as one of several set texts. I have told you that story I think. During the preliminary read-through Joe quite understandably took the part of Othello himself. He also took the part of Iago since ‘You’re all too young to know what real malice is’; and of Desdemona, since ‘you’re all too young to understand the first thing about women.’ And so on through the main parts. The lesser parts he was prepared to distribute among the class, beginning with Bianca, which he assigned to one Graham Gates, sitting at the back of the form-room. Inevitably the shy but cheeky hand of Gates went up: ‘Please sir, what’s a strumpet?’ ‘A strumpet,’ Joe blasted, ‘is a musical instrument you play in bed, boy!’

It took the best part of the term to complete the read-through, Joe frequently breaking off to bring his real erudition and theatrical understanding to bear on a single line or phrase, but there was never a dull moment. One actually looked forward to a Joe class with relish, which could not be said of some other members of staff: Brian Stephan for example – an intriguing teacher if you were on his wavelength, but one who did precious little to put you on his wavelength. Joe got you on his wave-length within minutes, not least because he had the knack of knowing his pupils’ wavelengths – a process fraught with spontaneous psychology and mystery in equal measure.

As well as Shakespeare Joe guided me through Browning and (most of all) Yeats – a poet I have never ceased admiring since. I can still hear Joe declaim, with that touch of wistfulness that was his hallmark as a reader:

Under bare Ben Bulben’s head

In Drumcliff churchyard Yeats is laid.

An ancestor was rector there

Long years ago, a church stands near,

By the road an ancient cross.

No marble, no conventional phrase;

On limestone quarried near the spot

By his command these words are cut:

Cast a cold eye

On life, on death.

Horseman, pass by!

Joe’s understanding of Yeats was based on one of Yeats’s own perceptions, that poetry is born of the ‘quarrel we have with ourselves’. I have sometimes wondered about Joe’s own inner quarrels (and we all have them) as the source of his great but often provocative wit and prodigious talent as a theatrician (to coin a phrase). For what it’s worth, and from this late vantage point, it strikes me that he was poised between the pursuit of (for want of a better term) respectability, even status, and an almost anarchic bohemianism. But he never allowed these opposites to destroy him. Rather he managed both stations with considerable aplomb (and, as I wrote before, with your unfailing support during the retirement years). Except for very small children he could mix with pretty well everyone, and had that enviable capacity to draw the unsuspected best out of those who were fortunate enough to experience his conversational powers. He could make one say things one had never thought of saying before, and feel good about it.

Between leaving Stowe and your arriving in Tenby at the end of 1989 I saw Joe but rarely – maybe once every four or five years on average. I am however proud of the fact that I succeeded in persuading him to contribute a clutch of essays to my culture books – Browning, Tennyson, Rostand, latterly Housman and MacNiece, above all Yeats. Many of the other contributors were distinguished professors, but Joe’s pieces matched, and in some instances more than matched, theirs. Amongst all his other talents he was both an exacting scholar and a skilful writer – a combination examples of which do not abound.

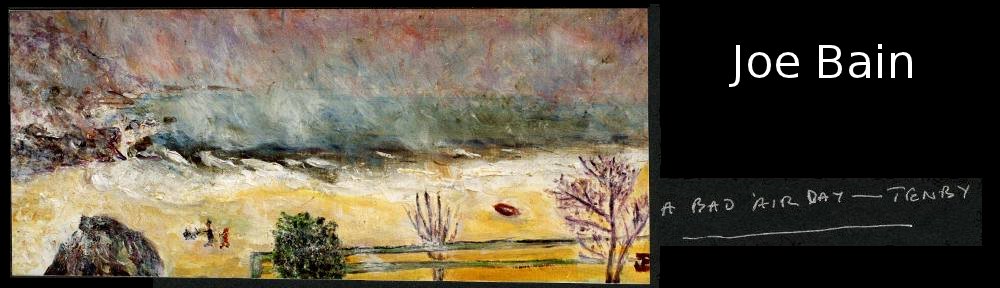

And then came Tenby, and the first dinner at No. 7, accompanied by a rare and costly wine. It was not something I deserved, yet I drank and continued drinking. During his address David Rowe-Beddoe most appositely re-iterated a comment Joe made to me more than once, that he considered himself fortunate to have led two lives, one as a teacher in England, one as a Welshman in his native land. And now it was the second that came to the fore. Hand on heart I can tell you that my biography of R. S. Thomas would have been a very different book without Joe’s participatory encouragement. As we traipsed hither and thither all over Wales in search of the roots and promptings of that sour genius, Joe’s deep knowledge of Wales and the Welsh provided the context and perspective I doubt I could have found by myself, certainly not within the time-frame commanded by my editor at HarperCollins (another Welshman, Philip Gwyn-Jones).

One aspect of that quest was Joe’s relentless quizzing of shopkeepers, whether in Haverfordwest, Eglwysfach or further afield in Aberdaron. He hunted down serving Welsh speakers with the tenacity of a big cat hunter, and when he found one never let go until he had prized out some or other arcane gem.

Hanging around with Joe in Wales was the most civilised of pursuits. But of course the time came for me to return to London, and to the ever-patient Kimiko, in 1997. Yet that was not the end of what for me had become an immeasurably important and uniquely valuable friendship. Right up to the end, when I wasn’t gallivanting around somewhere east of the Irrawaddy, Joe and I had routine late night telephone conversations, shooting the nocturnal breeze about books, music and most of all people we knew in common, or of whom neither of us had any personal knowledge at all. Tony Blair, for instance, or Boredom Frown. There were also interludes of purest fantasy. Joe had a thing about there being no great lady composers – odd since there are so many gifted women writers. Out of this grew an entire alternative cast – Betty Beethoven, Mandy Mozart, Wendy Wagner, Sheila Schubert, and so forth. And it did not stop there. We then endeavoured to imagine the compositions such composerines might have produced.

I sometimes thought I should have, and in retrospect wish I had, made notes of some of Joe’s endlessly entertaining and often outlandish lucubrations; but that perhaps would have been against the grain of the spirit in which such conversations were held.

Eheu fugaces. Once in a while Joe would grace our metropolitan tent with a visit. It was a source of deep pleasure to me that Joe became, and remained, a great ‘favourite’ with Kimiko – no wonder she cried when Joe’s ashes were eventually interred. Kimi brought out Joe’s charm, and vice versa. And nothing in this dull sublunary world counts for more than charm I hazard.

Deborah Stuart, (née Mounsey) writing in November 2011:

I was indeed very fond of Joe, we go back a very long way and I had a lovely quirky letter from him about a month before he died. They used to arrive infrequently, nearly illegible but always welcome, amusingly different and delightful. Before that I heard from him when Colin James died, Joe had seen him and they had had a jolly lunch together in Winchester about 3 weeks before Colin slipped off the mortal coil. – I have no idea what Joe was like as a teacher, but as a friend he was peerless. Helpful but not nosey, endlessly amusing, and full of life-enhancing qualities that are invisible but present. He was a key part of a small group of young Stowe teachers who made up a select circle of my parents’ friends – it included Colin James, Simon, John Hunt and Michael Vinen, I think his name was Michael, they used to come to The Old Brewery House for supper. A smoker’s den of catty, witty and silly gossipers. All of them slightly, or very, enamoured of my mother. I do remember him on the steps of The Queen’s Temple, producing Macbeth (or something), Mummy and the Art School were doing the stage props and scenery – it was sunny and everyone was being rather tiresome, Joe bellowing! And there is another Stowe story about one of Joe’s productions when some hapless Thespian stepped out bravely to his cue only for Joe to bellow – “Invisible, inaudible and the Wrong Boy!” – I loved Joe for his kindness and understanding, he never bowled a googlie. He was fun to be with and his laugh was unforgettable. - Picnics were alcohol and cigarettes beside a road, I don’t remember him providing any food – I did that if I knew in advance we were going more than a mile or two. The horrible alternative was Joe, driving at full speed, while fishing under the seats for the cigarette packet, and then in his pockets for matches which was suicidally dangerous. – Priscilla and Joe, plus a few others, were on one of my honeymoons. That is to say, I was on their holiday – married to Simon. It came about thus: Joe and Priscilla plus 5 others, one of whom was Simon, all planned to spend a month in Germany/Austria at the Munich and Salzburg music festivals, and they all stayed in an inn at a town called Hof. Between the booking and the event Simon married me, so I came too. Bear in mind that this meant that one person for EVERY event had to give up a ticket, this was going to be a ticklish situation. One day, when we had nothing much to do during the day, the whole party went off for a picnic near a lake. After a lot of swimming and general lying around Simon went off on his own to climb a nearby hill. Eventually, the rest of the party left, all except Joe and me and Simon up his mountain. I had a car and no keys, and Joe had a car. Priscilla and Harry Williams, who was also part of the crowd, went off with one of the others but Joe insisted on staying with me. By this time ALL the German families had gone, there was just the lake and us and the increasingly worrying absence of my husband. Finally Joe too had to leave in order to get back in time to change etc. etc. for whatever concert they were going to. I had to beg him to leave. After another hour and a half when it was definitely getting dark, Simon reappeared. We were now exceedingly late and had to drive (Simon at the wheel) at a terrifying speed back to Hof. As we raced up streams of traffic (the Germans do not lightly give way to overtaking cars) I think we saw Joe hastening back to find me/us. Since the episode had been fraught it was politely never referred to again, so I have never been sure. But there were not many English cars on the road being driven by men in dinner jackets and bow ties, I feel sure Joe had come back on a rescue mission. – As for the Liszt rhymes quoted by Michael Fontes at the Winchester service, there was a ruder, briefer one:

Liszt pissed into the pianoforte

- Naughty!

Both Joe and Simon claimed it!

Tommy Cookson, former Winchester don – from a letter to Priscilla Bain , 25 October 2011:

… [Carol and I] both felt that our time at Winchester was made so much more enjoyable, amusing, interesting and warm when Jo joined the staff. Quite apart from his learning and intelligence which were formidable, and which ratcheted up my education by several notches, he was the best companion you could ever want. I remember him coming to supper at Hopper’s with Jonathan and Jane Miall (Jonathan was at Stowe in Jo’s time) and Jo simply got going in the way only he could till the rest of us rolled around with laughter – it was a sort of cumulative effect, Jo getting funnier and the rest of us getting weaker. Winchester, I think, must have seen him at the top of his game as he could take the teaching in his stride, didn’t have the fatigue of housemastering having done it at Stowe, and could really be himself in an atmosphere he enjoyed. He had an instinctive understanding of Wykehamists and they loved him – who will forget his playing the part of the genii in Aladdin, coming on with sparklers in his pockets and a plastic fried egg round his neck, and the roar which greeted him – ahh, it was very special. When I was the don editor of The Wykehamist we had Jo, Martin Scott and Neville Grenyer on the cover of the Christmas edition wearing paper hats and blowing those things that come out and make whistling noises – as if there were any other members of the Common Room who could evoke the same festive feelings… I suppose someone could find a copy of it to have lying around at the Memorial Service just to remind everyone (if they needed it) of the sheer fun he brought to the place.

Whether it was in setting Scholarship papers (at which he excelled) or at Departmental Meetings where he was always perceptive and respected, or producing plays (I remember doing the Jane Austen evening and the Keats evening with him) or his talking about writers which had the effect nearly always of one’s wanting to go away and read them, he was an inspirational colleague and the more I knew him the closer I felt to him. On one occasion we had been invigilating an exam in School and he suddenly challenged me to a race to the Old Common Room. I was younger and slimmer, but I only just squeaked home in front. Amazing! And extremely friendly in a sort of way.

He will be hugely missed – one of the great characters and teachers Winchester was privileged to have.

James Cellan-Jones, writing in December 2011:

Joe and I went up to Cambridge in 1949. Joe had been in the airforce where he learnt to type unlike me. We neither of us did much work though it mattered more for me as I was reading science. Neither of us was a very good actor though we were both obsessed with the theatre. Joe was a brilliant sight reading pianist: he made you think his mistakes were deliberate. We acted in the Footlights in 1951 and numerous other plays always in small parts though I remember a rather iffy Importance of Being Earnest when Joe played both the manservants, Lane and Merriman, both better than the leads. Curiously neither of us thought of directing; I only started when I was a recruit in the army when I had to hide in the latrine to write the script.

We kept intermittently in touch over the years; he asked me to direct the Stowe show one year but I couldn’t do it as I was making a film. In 1979 he asked me to judge the Queen’s medal for verse speaking at Winchester. I had just finished being Head of plays at the BBC and returned to directing. One of the boys asked “Sir ,why didn’t you get someone who is someone rather than someone who was someone?” “Ah Wykhamists, Wykhamists,” said Joe .The event went quite well. I liked enormously the Head Master Dr Thorn who cried copiously and wanted to give all the boys a prize. The medal was won by a boy who recited Fern Hill by Dylan Thomas; in the judgment, I said that when he spoke of the spellbound horses walking warm onto the fields of praise, Thorn, Joe and I were all snivelling though Joe conceealed it best.

Afterwards Joe said “I’m giving a German lesson in my house, do you mind watching?” “My German’s a bit rusty”, I said “but I’d be interested to see you teach.” I think he said, “Every fool to his fancy,” though I can’t swear to this. Joe’s living room was festooned with fifteen year old boys; he managed to include each one in the lesson; he was open, spare, speedy and amused; he appeared less a pedagogue than an indulgent elder brother. When the lesson was over and I’d said Auf Wiedersehen to the boys, I said “They’re awfully good. How long have they been learning German?” “All term ” he said “six weeks.” “That’s remarkable,” I said. “Ah well,” said Joe ”You’re not a Wykhamist.”

I shall miss him a lot.

Muir Temple, writing in December 2011

I first met Joe when we both went up to Cambridge in October ’49. Almost my first memory of him is of the day when he enlisted a small group of fellow freshmen to help him to move an upright piano into his room in St John’s first court. The staircase was about an inch larger in all directions than the piano and there was much sweating and swearing before, to Joe’s imperious encouragements, we got the thing into his room. I never heard him play. Years later he received the ultimate accolade when Peter Longhurst (not perhaps the subtlest of critics) was bemoaning the expense of having Brendel at Stowe when Joe, ‘would have done it at least as well and for nothing.’ Other musical memories include, as his under-housemaster, trying to steal away after doing dormitories before being caught to identify the singer of Zerbinetta’s aria or to listen to the last act of Gotterdammerung. And playing the cuckoo (and the fool) in the Toy Symphony under Joe’s baton.

I think we all found him pretty awesome [in 1949]. In the first of a series of lectures by Dr. Bolgar to Mod. Linguists each of the several dozen freshmen and women was handed a sheet with about fifteen quotations from French literature to identify. Most of us, fresh from national service, floundered in bewilderment. Not so Joe who was also the only student to spot that one of the quotations was a translation into French from The Waste Land.

In the first term of our second year Joe and I attended supervisions in Dr. Lough’s tiny sitting room with sun streaming through a French window and an electric radiator with all bars full on. In this torrid atmosphere we read out our weekly essays to the accompaniment of Dr. L’s sucking on his moist tobacco pipe. Mine were brief and insubstantial. Joe’s were erudite, lengthy and delivered with great vehemence. This experience, I think, was one of the reasons why we both changed faculties in mid-year, he to read English, I to Arch. and Anth. Thereafter for the next year or so we drifted apart. Joe was much involved with the theatrical set.

Mercurial wit such as Joe’s is ephemeral and, divorced from context, loses much or everything. Housemasters’ meetings, hardly sparkling affairs, were occasionally enlivened by Joe as in the example quoted by George Clarke at the memorial service and as, when Stuart Morris , making an impassioned plea for an all-weather hockey pitch, added “It’s high time Stowe had a Sports Complex,” there came a growl from deep in Joe’s armchair “I thought we already had one.”

As you know, Joe provoked laughter wherever he went. Only on one occasion was this unintentional. At the height of the Profumo affair there was a boy in Chandos called Keeling. After lunch one day Joe made one or two announcements and then added very firmly “And I want Keeler in my study NOW.” It brought the House down. Joe was always ready and quick to spot incongruities. He arrived up here having driven for some miles on our twisty roads behind a van on the back of which there was the alarming objurgation:

BRAKE

AND CLUTCH PARTS .

I have two other memories of Joe as a driver. As Priscilla may have mentioned, Joe was instrumental in my moving to Stowe in ’58. My wife and I remember with pleasure our first experience of the place as he drove us in his open car on a gentle and comprehensive tour of what was then a romantic wilderness. Some years later he drove us in Priscilla’s Alfa Romeo to Simon Stuart’s post-wedding luncheon party at the Park Tower Hotel. We were mildly surprised that Priscilla insisted on taking a back seat. After lunch we discovered the reason. From the car park beneath the hotel Joe drove up the spiral ramp at an ever-increasing rate until we debouched without a pause into the rush-hour traffic and raced northwestwards, zigzagging through every gap with incredible and terrifying skill and daring, until we reached open country where, there being no further challenge, he drove sedately back to Stowe.

I miss my frequent phone conversations with Joe in which we each tried, with varying success, to jog the other’s memory. I enclose a photocopy of the cartoon in the Epicurean of 1962 when Joe was still a beardless boy. The Bald Prima Donna, incidentally, was brilliant but not to everyone’s taste and at least one Housemaster stormed out of the Roxy in a fury. Was it after this production that Crichton-Miller’s only comment to Joe was that the car-parking arrangements had been unsatisfactory?

Jill Watefield, 2012: A glimpse of Joe at Cambridge in 1952

It has to be remembered that food was still rationed when we were up [at Cambridge] & Joe’s landlady in his degree year at 13 K.P. [King’s Parade] on the first floor over a shop, & looking over K.P. to the frontage of Kings, obviously ‘took a shine’ to this gorgeous young man & provided him with as full an English breakfast as could be managed. But he didn’t want to eat breakfast so he stole down through Kings to the Cam & tipped it in so as not to upset her. And at Newnham we were collecting all sorts of horrors from the hot cupboard!