Peter Yapp – (Stowe 1958-1962)

Tribute to Joe Bain in at the Memorial Service in Stowe School Chapel, 10 September 2011.

[An extended version of what I said in the heat of that moment - editing on my feet so as not to overlap with other speakers.]

I shan’t keep you as long as Joe did if he lured you for a late night chat at any time in the last fifty years, and alas I shall not be as entertaining as Joe because so much of the word-play which effervesced as he spoke kindled on the context of the moment and lingered only as long as the smoke from his cigarette. Come to think of it, the smoke was more persistent. I pointed out in a Kings Road antique shop window a beautifully carved kitschly sub-pornographic nude nymph in marble, poised as if about to plunge into an invisible pond at her feet: ‘Lady Go Diver,’ said Joe, faster than thought.

Joe was my first form master. He was not quite thirty – but I didn’t notice that at the time. It was not an auspicious beginning: I wrote home that the classrooms echoed so that you had to concentrate all the time to keep abreast of the lessons, and that the masters appeared to be ogres without human feelings. Joe set us our first essay for him: ‘It is better to travel hopefully than to arrive,’ and we plunged into an analysis of Browning’s Last Duchess – and started reading a French comedy, Dr Knock. I was in way over my head. There was always a sense of danger about Joe and at first one didn’t realise how much of his exasperation was just part of the toolkit. Justin Wintle later put up his hand provocatively: ‘Sir I can’t read what you’ve written at the end of my essay.’ – Snatch – ‘It says I can’t read your handwriting … I’ll throw you out of the window!’ A threat repeated on another occasion.

Fast-forward four years through much French, some English, two Congreve club drama productions – and by my last term he was teaching me basic Italian out of hours, with Twelfth Night to come . The thankless task of formally teaching me was over – now I was to be treated as an apprentice friend. Part mentor, part Lord of Misrule, he allowed himself more indiscretion: When he took me to Verdi’s Forza del Destino we noticed a line in the programme synopsis: ‘He offers them fame, fortune and sexual favours.’ – ‘Sounds like your housemaster exhorting the First Fifteen,’ said Joe. – During the Xmas hols. in my last year he and Simon Stuart took two of us out to supper. We found them very glum in Simon’s flat, lamenting that they weren’t really schoolmasters, they were dons manqués. And we descended to the street where Joe vaulted over two dustbins and Simon climbed the railings and sprinted the length of Brompton Square’s garden.

By the time my brother David and I had passed though Stowe Joe had become a family friend as he did to the Cartwrights and Wintles in our generation and to many others in other cohorts. So we learned that it was not just in the classroom that he was always on his feet – and the image of Joe in later years standing in front of a mantelpiece, glass in one hand, cigarette in the other is so vivid that memory plays tricks and recalls him thus in the classroom. You can’t quite see from the photo of Joe on the phone on the service sheet that he’s got the glass and the cigarette into one hand in order to field the further prop. The low rumble – in later years just a bit more – Welsh – the sly glance as he made a point, the unexpectedly high chuckle celebrating the latest fun…

We were lucky in our teachers – at least two of you who infected me with their love of their disciplines are here today – and if I mention along with Joe, Bill McElwee and Simon Stuart it is not just because I saw more of them – but because all three taught as performers – Bill with the slightest Svengali element foreign to the other two , channelling history, in conscious role-play of gentlemanly character – deliciously raffish gentlemanly character – Simon perhaps because he’d been very ill before he came here, didn’t know if he would make old bones, and wanted everything which he cared about to be a festival – and Joe, I think now out of human melancholy and misplaced mistrust of his own abilities, consoled and enchanted by the life of the mind – of many minds – but so cheered by the innate ridiculousness of everything that fun would keep breaking through – so that from his most rigorous teaching effervescent laughter escaped. His evolution of form was fascinating too: the clean-shaven cherub we first met had already evolved from the cross bony boy Priscilla found in a Marlborough photograph: scowling, arms stretched to knuckles on knees – recognisable to me now only by that frown and its intensity – through the beard in its many forms, as his red head whitened – a beard Priscilla tells me was inspired by finding himself at a house-party of Simon Stuart’s on Eigg where there was nowhere to plug his razor in and realising that precious time could be saved at the awful moment of beginning a school day. When the then-headmaster Donald Crichton Miller first saw it he exclaimed: ‘Haw! Self-expression!’

He was a housemaster after my time – and I must leave Peter Arbuthnot and others to speak of that – but I am rather disturbed by the gallant references to floggings survived: fortunately Joe never beat me to anything but a joke. And I think more of his professional dedication than his enthusiasm went into school sports. Justin Wintle retired to the rugby touchline with a squashed and bleeding nose. When Joe – a spritely referee then – noticed, he just said: ‘That’s the first time you’ve looked like a rugby player,’ with a grim relish of the awfulness of it all.

My annotations in a script trace Joe’s attempts to to inject variety into one-note performance: ‘Keep it light, it’s routine,’ … ‘sincere, no more fun,’ … ‘Don’t do the hard labour all the way,’ … ‘Almost whisper … fade … gasp.’ – ‘Don’t do the hard labour all the way,’ is a great general acting note. - I was trying to be a Jesuit in The Strong are Lonely: ‘You’re going to be neurotic Father Provincial rather than a strong one.’ – But he cast me as twins next time round, so it can’t have been all bad. Some of his later notes on children were notable too: ‘You must read to them all the time. Doesn’t matter whether they enjoy it – it goes in. And it must be the mother. Fathers show off,’ – with a glance at me.

Only now, helping Priscilla with Joe’s family papers have I really understood how the mother who read to him had been influenced perhaps by the remarkable grandmother he never knew, whose companion she had been, and how greatly loved a master Joe’s father was at Marlborough. His ex-pupils wrote many letters – and far too many died in World War 1. John Bain wrote elegiac poems for each one, sent to their families and published in the Marlburian, and celebrated this year in an article by J.A.Mangan, historian of sport and the ethos of empire. They’re good poems of their kind, too. John Bain was over seventy, retired, when Joe was born, and died within a year or so. – The DNB article on John Bain’s brother, Joe’s uncle, F.W.Bain – an eccentric scholar of that generation – quotes a description of him in conversation at All Souls which sounds very like Joe in full flight. And the introduction to the revised edition of grandfather Joseph Bain’s Calendar of Scottish State Papers is entertaining about Joseph’s occasionally over-optimistic solutions to problems of translation, dating and attribution. Joe wasn’t an accident: it was in his bones. His own scholarly judgement was meticulous: as his articles on the Roberts Bridges and Browning , on Edmond Rostand and W.B.Yeats in Justin Wintle’s, Makers of Moden Culture show. If only he had written much more – but he wasn’t a lecturer: he existed in dialogue – was fuelled by response – and was a master at keeping permitted impertinence in a formal setting to a level where it stimulated a lesson rather than derailing it.

He led me through Winchester College at night to show me the set for Black Comedy – a play with a bright-lit stage for audience on which characters move in the dark of a powercut. It’s a nightmare to rehearse. ‘People ask what they should do as house plays. Anything I say, except farce. And what am I doing… They all speak too loud. They don’t listen to my notes.’ It was his forty-somethingth production. – I saw the Fidelio he staged with Angus Watson: it was tremendous. Winchester stretched him: but he was wistful about the social life of Stowe: ‘Out there in the wilds the Master’s Mess was more like an army mess – or a London club – a very seedy London club, mind you…’ And the tales he told of his more eccentric colleagues in later years when discretion permitted were a hilarious alternative sociology of one’s impressions of what had actually gone on.

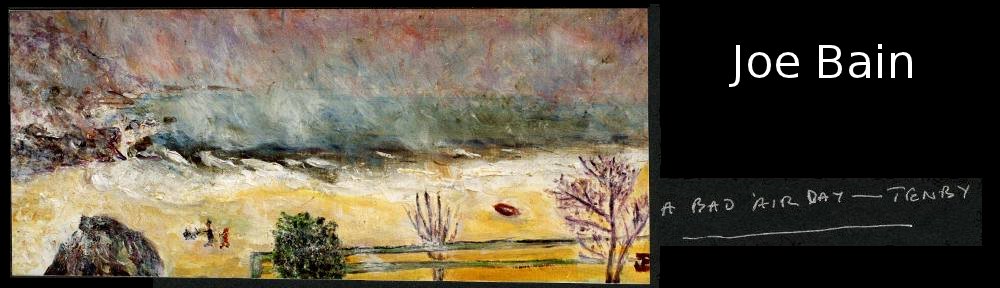

In Tenby from 1989 – in the marvellous house above the sea which seemed the flower of which all his previous quarters had been the bud – perhaps to Priscilla’s dismay as his library threatened to rise up beyond the bottom two of five floors – he announced that he’d started to paint: ‘I’m becoming the Grandma Moses of Tenby’. He wasn’t as good a painter as he was a pianist – but his technique noticeably improved – and there were Joe Bain jokes and visual/verbal puns in many of the pictures. ‘I’ve been painting your Kate since you left. Oh dear, she’ll never speak to me again … well, I paint people not as they are but as they will become – but this one – at the moment it looks a bit like like Dr Jonathan Miller. Perhaps I’ll send it to Jonathan Miller… Good heavens people say, who’s that? … Oh dear, it’s meant to be me…’

You could never tell how seriously he took some of the hobby-horses of his later years. He insisted Shakespeare was a front-man for others: didn’t have the education, couldn’t have done it. He had been misled as a child because the maid in St David’s blacked the faces of the busts of Shakespeare and Erasmus in the hallway with boot polish to make them easier to clean, so Joe thought both were Africans to start with… We progressed as to authorship, year by year past Bacon, the Earl of Oxford, the Southampton circle, &c – and at last came to a committee based at Petworth under the Archbishop of York. I tackled him about this: Come on Joe: what do you really believe? – ‘Well, it’s like the Bishop of Durham and God – now you see him, now you don’t.’ – But later, as if this had been too great a concession. ‘If I ever get to heaven the first thing I shall say is, Take me to Shakespeare – all of them.’

Well, there was only one Joe Bain and as a rabbi said at the funeral of another outsize character: ‘We will all go on telling these stories, and if as the years go by the stories get a little bit better, that in itself is a tribute’ – to Joe in this case.